Category: Safety

Gender smart safety in Papua New Guinea

An innovative partnership between International Finance Corporation (IFC), St Barbara and the Business Coalition for Women (BCFW) in Papua New Guinea has helped to build a safer workplace for female employees working at the Simberi gold mine. The implementation of a “Gender-Smart Safety” program in 2016 resulted in an 18 percent increase in the percentage of women who feel happy about their safety at work.

You might be wondering what it is that makes a safety program “Gender-Smart?” The program involved training a cross-functional team of employees from human resources, safety and housekeeping on how to conduct safety audits to identify risks and hazards faced by women in the workplace. Factive played a key role in researching and developing the Gender-Smart Safety initiative.

This trained team at the Simberi gold mine was able to identify risks specific to female employees that had not been identified using business-as-usual safety practices. By identifying these risks, the team was able to put mitigation strategies in place and monitor their safety performance against a set of key performance indicators.

For more information on IFC’s work on gender in East Asia and the Pacific visit their website here. A summary of the Gender-Smart Safety program (pictured) and how it is helping to create safer workplaces for women at St Barbara’s gold mining site in PNG can be downloaded via this link.

Workplaces free from bullying and sexual harassment are good for business

Factive is pleased to announce the official launch of the report: Respectful Workplaces: Exploring the Costs of Bullying and Sexual Harassment to Businesses in Myanmar.

The study was carried out by the Factive team in Myanmar on behalf of International Finance Corporation (of the World Bank Group) and DaNa Facility between September and November in 2018 to understand the experiences of employees relating to bullying and sexual harassment in Myanmar workplaces. There were 39 participating organisations, including 26 large businesses in the agribusiness, finance, retail and tourism sectors.

Some of the key findings of the report:

- Sexual harassment affects all workplaces. 21 percent of employees said they had witnessed an incident of sexual harassment in their current workplace.

- Bullying is more common than sexual harassment. More than half of the employees said they had witnessed an incident of bullying.

- Bullying and sexual harassment are a significant cost to business. On average, the study found businesses experience a 14% loss to labor productivity due to presenteeism caused by bullying and sexual harassment.

- Businesses are not adequately prepared to respond. Very few businesses had formal policies and procedures in place. The vast majority of employees do not report incidents of sexual harassment and bullying. Instead, they ignore them or discuss them on social media.

- Bullying and sexual harassment are workplace culture issues that can be addressed. There were considerable differences in the levels of bullying and sexual harassment across the 26 large businesses. This contradicts the common excuse that these disrespectful behaviors are a natural part of Myanmar culture.

The report offers business leaders in Myanmar an opportunity to understand the experiences of employees relating to bullying and sexual harassment in their workplaces. It also provides a set of practical recommendations, targeting business leaders, human resource managers, employees and other interested parties, to help create workplaces that are safe and free from bullying and sexual harassment.

The report was produced by IFC’s Gender Secretariat in partnership with DaNa Facility. You can download a free copy of the report by visiting IFC’s website. Both Burmese and English versions are available.

New research article on women’s safety in Papua New Guinea

Our principal consultant Dean Laplonge has published a new article based on his work exploring safety for women who work in remote locations in Papua New Guinea. This work has been completed through Factive’s client the International Finance Corporation, and in partnership with the Business Coalition for Women in PNG.

Article Title

Responding to paternalistic protection: Gender-smart safety for women working in remote locations in Papua New Guinea

Abstract

The practice of a ‘gender-smart safety’ is an important part of recognizing and responding to specific risks faced by women in workplaces. This is a relatively new concept within the discourse of workplace safety, and one that is challenging traditional views about what safety is, how it should be managed and who should be included in this management. This article explores the findings of a research project that looks at the safety of women who have experience of working in remote locations in Papua New Guinea (PNG).

You can access the article here.

What does diversity have to do with extractive industry disasters?

Yassmin Abdel-Magied argues that a lack of diversity was responsible for the Deepwater Horizon oil disaster in 2010.

“Was there anyone else around the table who thought differently and who didn’t just think differently, but was included enough and was valued enough so their different perspective was valued, to actually challenge that bias?”

“Everyone around the table came from a similar world and a similar perspective. They all thought the same. They all cared about the same things. And so we ended with one of the worst tragedies in our industry.”

Read the full article HERE.

Factive’s Director and Principal Consultant, Dean Laplonge, is currently exploring the link between masculinities and mining disasters for a chapter in his next book. To discuss this issue with Dean, contact him through our website.

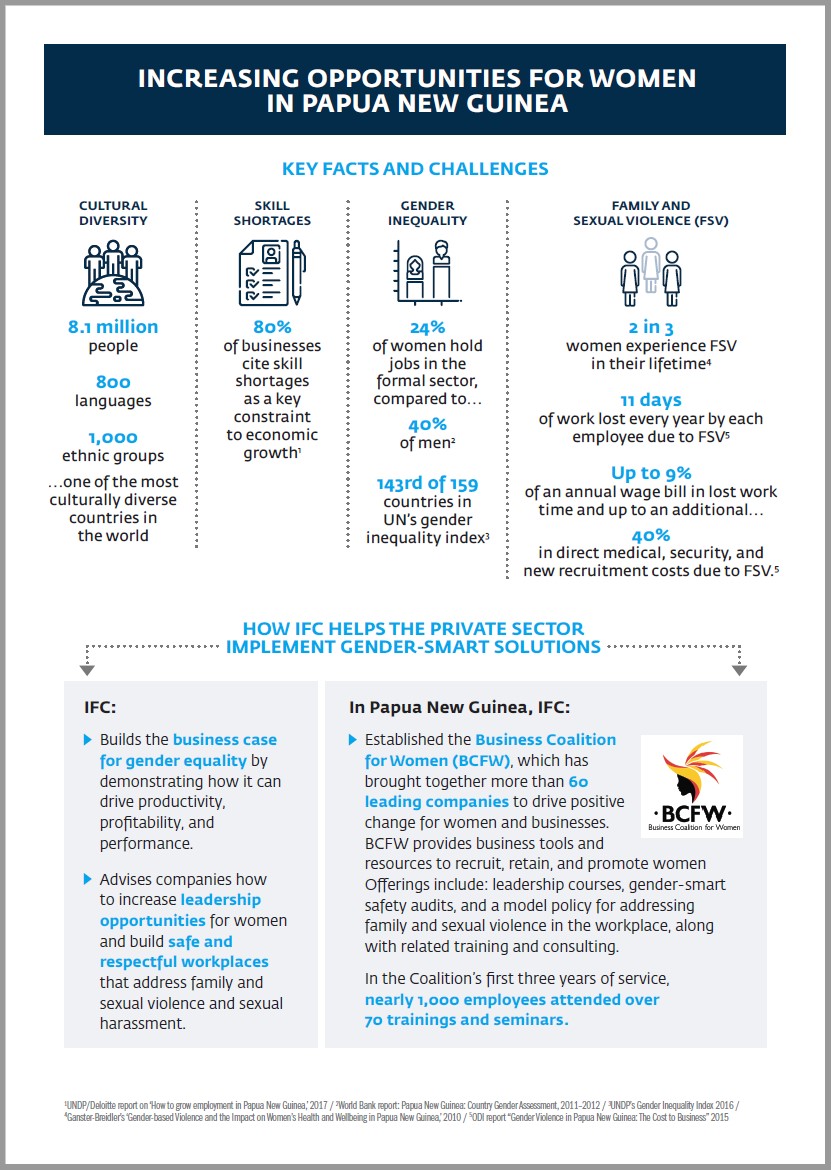

Gender Smart Solutions in PNG

Factive continues its work with the International Finance Corporation and the Business Coalition for Women in Papua New Guinea to support Gender Smart Safety in workplaces.

A new article published in the Annual PNG Industry Overview 2017-18 by Energy Publications provides information on the services and training programs the Coalition offers to member companies.

The impetus for the development of the Coalition’s Gender Smart Safety resources was the realisation that some women were being overlooked for career development opportunities simply because their employers felt they could not guarantee their safety on particular worksites.

Importantly, we equip PNG businesses with a sustainable approach to improving women’s safety by training their own teams and giving them tools to conduct women’s safety audits.

To read the full article online, click HERE.

NBPOL participates in Gender Smart Safety Audit

A women’s gender workplace safety toolkit is being put in place to look after the welfare of women working in rural high-risk industries in PNG.

Click here for link to press release.

PNG Workplaces Adopt Gender-Smart Safety

The Papua New Guinea Business Coalition for Women is collaborating with 3 of the largest companies in Papua New Guinea (PNG) to adopt Gender Smart Safety. New Britain Palm Oil Limited, Oil Search Limited, and St Barbara’s Simberi Gold Company Limited are participating in a new training program that will help them improve safety for women on their worksites.

“Gender-smart safety is a relatively new field of work,” says the training facilitator Dr. Dean Laplonge. “Employers are starting to see links between gender and safety in their workplaces. They are starting to understand how women often experience workplace safety differently to men. This is the first time gender-smart safety has been implemented in a PNG workplace.”

See the full press release here.

Is gender-pay inequity fair, due to work risks?

Mark Perry asks if achieving the goal of gender pay equity would be worth the loss of life for thousands of additional women each year who would die in work-related accidents.

The argument for pay equity is based on the claim that women do not get paid at the same rate as men for the same jobs. Because the number of workplace fatalities is less for women than men, are you making an argument in favor of occupational fatality equality?

The argument that women don’t get paid the same as men for the same job is frequently made based on the difference in unadjusted median weekly or hourly wages. The 17% gender pay gap is frequently used as evidence that women get paid less than men for doing the same job, which is of course false, but incorrectly used by feminists and gender activists. The National Committee on Pay Equity makes no adjustment for any differences in pay other than gender discrimination. Using this flawed feminist/progressive logic about the gender pay gap that is used to determine Equal Pay Day, I similarly use that logic to determine Equal Occupational Fatality Day based on the assumption that the goal of the feminists/progressives is to close the gender pay gap to zero.

In reality, I believe the gender pay gap is pretty small, possibly statistically insignificant once we control for all of the variables that affect earnings, including hours worked (men work more hours on average than women), continuous time in the labor force (women are more likely than men to have interruptions in their work experience), types of occupations chosen, etc. I also don’t believe that it would ever be realistic to close the gender occupational fatality gap because it is a well-documented fact that men have a much greater tolerance for risk than women, and will therefore always be disproportionately represented in risky occupations like construction, logging, commercial fishing, law enforcement, etc.

You argue that part of the reason for a gender pay gap is because “a disproportionate number of men work in higher-risk, but higher-paid occupations”. You then list some of these occupations: miner, fire-fighter, police officer, logger, construction worker etc. Isn’t your claim somewhat culturally specific and therefore limited? Do people who work in these kinds of industries always get paid more than other workers in all countries?

According to economic theory, supported by empirical evidence, it would be the case that workers in higher-risk occupations should be compensated with higher pay. For occupations that are physically demanding in harsh and risky conditions, there should be a risk premium; and for occupations that are inside and have very comfortable working conditions, workers would generally accept lower monetary wages for the benefit of pleasant, safe and comfortable working conditions. Like above, it’s an empirical fact that men have greater tolerance for risk than women and will gravitate in greater numbers to risky occupations than women.

How do you respond to the argument that women’s workplace safety has, in fact, been under-researched? The few studies that exist on this topic suggest that it is not that men experience more fatalities or injuries than women at work, but that the statistics on women’s safety in the workplace are not as readily available; and that investigations into workplace safety often don’t consider safety for women specifically.

I’ve never heard that issue raised in the US. The US Department of Labor (Bureau of Labor Statistics) provides very detailed statistics on workplace fatalities in the US, including a breakdown by gender. If anything, the BLS pays more attention to women in the workforce than men.

You conclude that “Closing the “gender pay gap” can really only be achieved by closing the “occupational fatality gap.” Can you explain this? In particular, can you identify what companies should do to realize this?

I am really being a little facetious, tongue-in-cheek and satirical when I say closing the gender pay gap can only be achieved by closing the occupational fatality gap. My point is that, if the feminists are serious about perfect gender pay equity, that could only be achieved by perfect gender equality by occupation, which would imply perfect gender work-related deaths. Another point is that part of the unadjusted gender wage gap in favor of men is that they are more willing to work in really dangerous, dirty, unsafe, unpleasant, physically demanding and risky work conditions, for higher pay of course. So instead of forcing women into those higher-risk, higher-pay occupations, we should instead realize that differences in gender preferences for risk/comfort/safety/ for working conditions is one factor, among many, that could explain gender differences in pay that have nothing to do with gender discrimination against women in the labor market.

A response from Dr. Dean Laplonge:

Mark’s suggestion is an interesting one—the possibility that statistics on gender pay equity do not factor in the element of risk taken by men at work. But it’s only interesting on the surface. It could be better explored, to think about whether women are willing to accept lower pay for doing less dangerous work. He could have explained how the data on gender pay equity ignores the issues he thinks are important. He doesn’t do that. Instead, he seems to be making the case for allowing men to get paid more than women, because he assumes they do more dangerous work than women. The issue of pay equity affects on women who are doing the same jobs as men. So, a woman who is driving a truck on a mine site is not guaranteed to earn the same as her male colleagues, even though they are doing the same job.

Mark’s argument also relies on essentialist ideas about men and women in relation to risk-taking. He doesn’t consider that women’s safety and risk-taking might be different to men’s. He admits to not knowing anything about women’s safety in the workplace—an important topic of research. He also doesn’t consider that risk-taking might be a way of doing man, rather than being man—which means that men take risks to show how masculine they are. Men can choose to NOT take risks; many do. And women can choose to take risks; many do.

It’s always worrying to hear people use the terms “feminist” or “gender activists” in a way that suggests we know how all these people think, and as if we are sure they all think the same way. I can assure you that if you gather a group of self-identifying feminists in a room, there’s unlikely to be agreement on everything! It’s also misguided to claim that men should get paid more overall because they engage in riskier work. Many women suffer injuries in the home which is a risky work environment. But they don’t get paid a cent for the work they do there.

Mark J. Perry is a scholar at the American Enterprise Institute and a professor of economics and finance at the University of Michigan’s Flint

Promoting safety of working women in Papua New Guinea

Factive is proud to be working with the Business Coalition for Women in PNG and the International Finance Corporation, to explore ways to better secure the safety of women who work on remote worksites throughout PNG. Factive’s Director, Dr. Dean Laplonge, will work closely with the Coalition and other stakeholders in PNG on this project.

Gender and safety has long been a focus for Factive and particularly for Dean in his endeavours to promote awareness of how gender impacts on safety in resource industries. This latest project is an important piece of work. It responds directly to existing gender-based problems that make life especially difficult for professional women in PNG. It also signifies a growing recognition of the important link between gender-based safety and gender equity in the workplace.

We look forward to working closely with local businesses and professional women in PNG over the next few months. We hope to be able to produce some effective tools that will allow businesses in PNG to make a step change in improving safety for their female workers.

This project is funded by the World Bank. For some background information, listen to a recent interview with Avia Koisen and Dr. Linda Van Leeuwen as part of the PNG Gender Parity Symposium held in Australia in October.

Men’s Experiences of Workplace Bullying

In this blog post we explore the topic of bullying in resource industries. This topic is of interest to us at Factive because it links into our broader work on gender in these industries. It’s also a topic that has received very little attention in the research and in organisational responses to improving workplace culture.

Our thoughts on this topic are inspired by a recent article: O’Donnell, S. & MacIntosh, J. (2015). “Gender and workplace bullying: Men’s experiences of surviving bullying at work”. Qualitative Health Research. O’Donnell and MacIntosh seek to explore the experiences of bullying among men at work. The sample of men included in their study is small; only 20 men in total. It is also very localised in that all the men who were interviewed live in Canada’s Atlantic Provinces. This study nevertheless helps to open up the debate about how men experience bullying in the workplace, and to respond to what the authors identify as a tradition of either exploring bullying only as it impacts on women at work or including the experiences of men as a way of comparing these to the experiences of women.

Their article is not industry specific; the men who participated in the study come from a range of industries. Its findings nevertheless allow us to think about how bullying might be experienced in very specific industries such as mining, oil & gas, and construction. It helps us ask a number of questions that need to be asked to explore how bullying impacts on men in these industries.

– To what extent does bullying take place in these industries?

– How do men in these industries deal with or respond to bullying?

– Are there specific reasons why men are bullied in highly masculinised workplaces, and do these reasons have anything to do with how men are expected to behave as men (or what might also be called “the policing of gender”)?

– What systems are in place for dealing with cases where men are bullied?

– Are these systems different depending on whether the bully is a man, a woman, a colleague, or a superior?

– Are these systems effective?

– What are the impacts of bullying in industries like mining on productivity, employee wellbeing, safety, and leadership?

In starting to think about this topic, we realise there’s a long way to go. Similar to when we first starting thinking about the links between safety and gender in mining, we discover that there are so many unknowns, and so much work to be done to understand this topic fully. The intention of this blog post, therefore, is to open up the conversation about men and bullying in the workplaces of resource companies. We anticipate we will come back to it at a later date.

There’s currently a lot of interest in the impacts of fly-in-fly-out (FIFO) on the personal health and well-being of workers. The FIFO model of employment is often appealing to resource companies. It enables these companies to tap into a much larger skilled labour force than is available in the local area. It can also mean the companies do not have to invest in building the community infrastructure that residential employees and their families often need and desire. In some cases, FIFO is actually the only option available, particularly if the resource operation is on an offshore oil rig or similarly extremely remote.

The current debate is, however, somewhat limiting in that it tends to emphasise how the negative impacts on FIFO workers are the result of their distance from their families. The assumption is made that FIFO workers suffer from mental health issues because they don’t have the support of family members while at work. This assumption is then reaffirmed by employees who see this as an acceptable way of rationalising their position when they are asked to describe how they feel. The “family” is often mythologised as stable and protective, and being away from this space therefore easily becomes a legitimate excuse for explaining why some FIFO employees feel unhappy or under stress. Questions about how the family space truly functions are missing in this debate. Importantly, there is also a lack of attention to how the cultures of the work environments may be causing damage to workers too. It may not simply be that FIFO employees are away from family members who might otherwise be able to provide support, but that the workplace where they are required to live for extended periods of time not only fails to provide that much-needed support, but actively causes discomfort and harm to them.

In male-dominated and highly masculinised contexts, for example, the demand to be appropriately masculine can be intense. It can take up a lot of time and energy on the part of those who are seeking to be seen as masculine enough and those who are intent on policing the masculinity of others around them. The research overwhelmingly shows that highly masculinsed cultures do not welcome or easily accommodate gender diversity. Behaviours and attitudes that are different to the established norms are discouraged and often bullied out of people. This is one of the reasons why many resource companies find it difficult to accommodate women in their workforce, as women are often instantly perceived to be insufficiently masculine and/or some women refuse to adopt what is deemed to be an appropriate masculinity so they can fit in.

An emerging idea in organisations today is the need for employees to learn how to become more “resilient”. Resilience training can focus on providing employees with skills in how to deal with difficult situations in the workplace so that these situations do not cause them stress. This kind of training is seen as a suitable response to help employees cope with stress while at work. There is a danger, however, that resilience training can offer an excuse to ignore the reasons why the difficult situations are there to begin with. Are employees expected to meet impossible demands for work production, for example? Is there a particular manager who is being unprofessional or even cruel with their staff? The demand for employee resilience too easily allows the organisation to avoid having to ask some difficult questions about its workplace culture. It also places the onus of survival on the stressed employee which is akin to saying that people who are intimidated or bullied just need to “toughen up”.

Yet, O’Donnell and MacIntosh identify that bullying at work comes in many different forms. It can be “manipulation, intimidation, humiliation, teasing, belittling, name-calling, criticism, blame, exclusion, isolation, punishment, oppression, withholding of information and resources, undermining work, credibility and reputation, removing work roles and responsibilities, altering work expectations, hampering or denying advancement, dismissal and threats of dismissal, yelling, and physical threats” (p. 3). What is particularly alarming from their study is the finding that the men who sought help from their employer to deal with the bullying all discovered that no support was available. The authors write: “There were no cases where seeking help from these sources [managers, human resource personnel etc.] resulted in workplace organizations taking appropriate steps to resolve the bullying” (p. 4). O’Donnell and MacIntosh further conclude that “speaking up resulted in negative consequences for targets, including having their integrity, reputation, and mental health questioned”. The workplace culture is, therefore, seen to be unwilling or unable to provide support to employees who are bullied. Insufficient work is being done to analyse why the workplace culture provides a space in which bullying occurs to begin with. Instead, individual men are left to deal with their experiences of bullying by themselves, and their responses can be as intense as leaving their job, severe depression, and suicidal thoughts.

One limitation of this study is that it focuses exclusively on the experiences of men who have experienced bullying. To understand why bullying occurs in the workplace, we also need to know how men who bully experience bullying. What motivates men to bully others at work? What do they perceive they gain and what do they actually gain by being a bully? Have they too experienced bullying in the workplace and, if so, how does this affect their attitude towards bullying in so much as they may not even perceive their bullying actions to be “bullying”? Are there specific kinds of people or behaviours they target, and why? A focus on the dominant entity (i.e., the bully) in this relationship of power between the bully and the bullied would bring this kind of research into line with the recent interest in exploring how the construction of dominant identities (e.g., man, white, heterosexual) function to reaffirm subordinate identities (e.g., women, black, homosexual) as “other”.

Given these preliminary ideas and thoughts on bullying in resource industries, the following are some recommendations for what resource companies can do to investigate the impacts of bullying on men in their work spaces:

1. Explore how employees understand bullying. This can be achieved through focus groups, surveys, interviews, and informal discussions in toolbox talks or similar. This provides a baseline for understanding bullying in the local workplace context, and it then becomes possible to compare the workforces understanding of bullying with what the legislation might say about bullying or about how bullying might be understood elsewhere.

2. Carry out a desktop review of relevant organisational policies which address bullying in the workplace, and consider how these can be updated to recognise gender as an important component of bullying. It may be that the organisation has no specific policies on bullying, in which case this might suggest a need to explore why bullying has been hidden or if employees who might normally be responsible for dealing with workplace issues of bullying lack the skills to do so.

3. Analyse the workplace culture to find out what kind of genders are dominant and what kinds of gender are excluded or ridiculed. (Here, the term “gender” must be seen as referring to how we behave as men and women, and not to biological sex.) This will help the organisation to explore experiences of bullying not as examples of bad people picking on victims, but rather as the outcome of a particular workplace culture that preferences specific kinds of people over others.

4. Ensure that senior managers and human resources personnel are adequately trained in how to recognise and respond to bullying, and how the responses might need to differ depending on whether the bully and the bullied are men or women. Safety professionals should also be included in this up-skilling and training, because safety and gender are recognised to be linked, and being bullied can place employees at greater risk of physical harm when at work.

If you have experienced bullying while working in a resource company or if you would like to discuss what your organisation can do to respond to bullying at work, please contact us through our website. If you have some comments or ideas about bullying in male-dominated environments, please write your comment here.