Category: Mining

Gender smart safety in Papua New Guinea

An innovative partnership between International Finance Corporation (IFC), St Barbara and the Business Coalition for Women (BCFW) in Papua New Guinea has helped to build a safer workplace for female employees working at the Simberi gold mine. The implementation of a “Gender-Smart Safety” program in 2016 resulted in an 18 percent increase in the percentage of women who feel happy about their safety at work.

You might be wondering what it is that makes a safety program “Gender-Smart?” The program involved training a cross-functional team of employees from human resources, safety and housekeeping on how to conduct safety audits to identify risks and hazards faced by women in the workplace. Factive played a key role in researching and developing the Gender-Smart Safety initiative.

This trained team at the Simberi gold mine was able to identify risks specific to female employees that had not been identified using business-as-usual safety practices. By identifying these risks, the team was able to put mitigation strategies in place and monitor their safety performance against a set of key performance indicators.

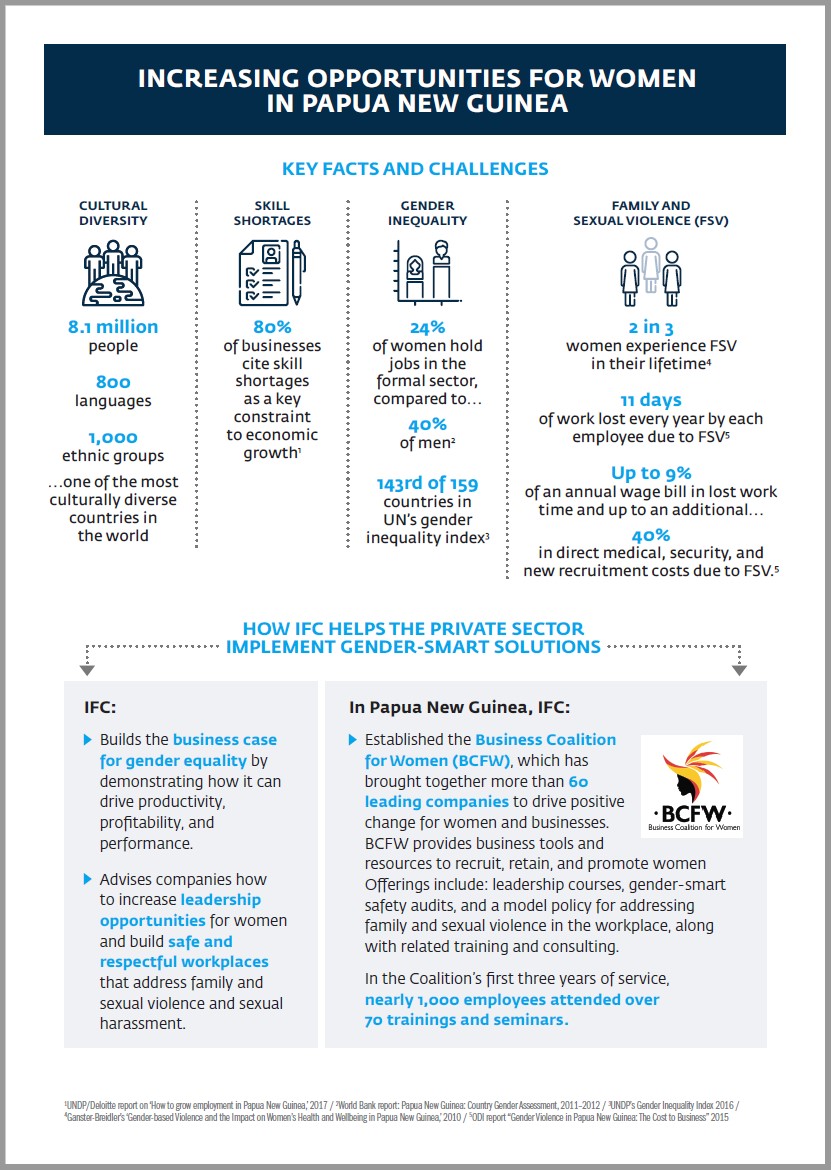

For more information on IFC’s work on gender in East Asia and the Pacific visit their website here. A summary of the Gender-Smart Safety program (pictured) and how it is helping to create safer workplaces for women at St Barbara’s gold mining site in PNG can be downloaded via this link.

Launch of #MiningTogether campaign

International Women in Mining (IWiM) is launching a three-month video storytelling campaign to promote gender equality and inclusion in the mining sector.

We know that many people will have examples of where their own actions, or those of a colleague, or their company, have helped to make the workplace more inclusive. Our campaign is about sparking a conversation around these inclusion moments across the mining sector, by encouraging everyone to tell us what they did and why it matters.

IWiM press release, February 28, 2019

IWiM, which was set up in 2007, supports thousands of women professionals working in the mining and metals sector. It is the fastest growing network for women in the mining industry. It has members in more than 100 countries, and supports over 50 Women in Mining groups around the world.

As part of the #MiningTogether campaign, IWiM is asking people who work in the mining sector to share their experiences of gender diversity and inclusion by recording a short video clip. These videos will be shared on the #MiningTogether – Inclusion begins with us YouTube channel.

“Gathering and sharing stories inspires us all to action. It helps us reflect and consider what have I done and what can I do in my personal capacity to make my workplace more inclusive. This is why we’re asking everyone to email us their short clips, telling us their stories.”

Muza Gondwe, Senior Projects Advisor, IWiM.

For more information about IWiM and the #MiningTogether campaign, see their website.

A successful strategy for reducing workplace bullying?

Glenn D Rolfsen is a psychotherapist and leadership consultant who works in the corporate health service in Oslo. In this TEDx Talk he outlines a simple and effective strategy for reducing backbiting within a group or organisation.

If you are wondering what backbiting is, Rolfsen defines it as “talking negatively about a third person who isn’t present”. In other words, it’s gossip.

In many jurisdictions, government regulatory bodies exist with the ability to deal with workplace bulling complaints. In Australia, this is the Fair Work Commission. The commissioner, Danny Cloghan, is on record as saying that:

“Bullying can manifest itself in many ways. I consider it uncontroversial to say that spreading misinformation or ill-will against others is bullying […]. Scurrilous denigration of a worker in the workplace would certainly fall within the boundary of bullying.”

Employers have an obligation to address practices such as backbiting in their workplaces. In some cases, this is so they can comply with workplace regulations about providing a safe work environment. In all cases, it’s to ensure these kinds of behaviors do not negatively affect employee well-being, employee performance and overall business productivity.

Here, Rolfsen presents his 6-step strategy for reducing backbiting:

In his Tedx Talk, Rolfsen quotes a short aphorism attributed to Socrates, which, although possibly a miss-attribution, is nonetheless instructive.

In ancient Greece (469 – 399 BC), Socrates was widely lauded for his wisdom. One day an acquaintance ran up to him excitedly and said, “Socrates, do you know what I just heard about Diogenes?”

“Wait a moment,” Socrates replied, “Before you tell me I’d like you to pass a little test. It’s called the Triple Filter Test.”

‘Triple filter?” asked the acquaintance.

“That’s right,” Socrates continued, “Before you talk to me about Diogenes let’s take a moment to filter what you’re going to say. The first filter is Truth. Have you made absolutely sure that what you are about to tell me is true?”

“No,” the man said, “Actually I just heard about it.”

“All right,” said Socrates, “So you don’t really know if it’s true or not. Now let’s try the second filter, the filter of Goodness. Is what you are about to tell me about Diogenes something good?”

“No, on the contrary…”

“So,” Socrates continued, “You want to tell me something about Diogenes that may be bad, even though you’re not certain it’s true?”

The man shrugged, a little embarrassed.

Socrates continued, “You may still pass the test though, because there is a third filter, the filter of Usefulness. Is what you want to tell me about Diogenes going to be useful to me?”

“No, not really.”

“Well,” concluded Socrates, “If what you want to tell me is neither true nor good nor even useful, why tell it to me or anyone at all?”

https://www.speakingtree.in/blog/socrates-triple-filter-test

IFC publishes new gender toolkit

Unlocking Opportunities for Women and Business

The IFC has published a new gender toolkit for Oil, Gas and Mining companies to assist them with the planning and implementation of their gender diversity initiatives. Published in May 2018, the 67-page toolkit provides companies with tools, methodologies and model policies to draw from when developing or reviewing their gender initiatives. The toolkit content is structured around four key issues:

- Increasing Gender Diversity from the Workforce to the Boardroom

- Women-Owned Businesses and the Supply Chain

- Women and Community Engagement

- Addressing Gender-Based Violence in the Workforce

It is refreshing and commendable to see that this toolkit moves well beyond the largely unsuccessful model of ‘women in industry’ type initiatives that have tended to be narrowly focussed on the recruitment of women into traditionally male-dominated industries. Instead, the toolkit encourages companies to look across the supply chain for opportunities to improve the participation and equity of women, such as using women-owned businesses. It also provides tools to help companies tailor their community engagement activities to ensure that women’s voices are sought out and listened to, and looks at ways to identify, measure and address gender-based violence in the workforce.

Further information

- Morgan Landy, Director, Infrastructure and Natural Resources, International Finance Corporation has published an excellent post on the IFC toolkit on the Business Fights Poverty website which you can read here.

- The IFC toolkit, UNLOCKING OPPORTUNITIES FOR WOMEN AND BUSINESS: A Toolkit of Actions and Strategies for Oil, Gas, and Mining Companies, is available as a PDF download here.

What does diversity have to do with extractive industry disasters?

Yassmin Abdel-Magied argues that a lack of diversity was responsible for the Deepwater Horizon oil disaster in 2010.

“Was there anyone else around the table who thought differently and who didn’t just think differently, but was included enough and was valued enough so their different perspective was valued, to actually challenge that bias?”

“Everyone around the table came from a similar world and a similar perspective. They all thought the same. They all cared about the same things. And so we ended with one of the worst tragedies in our industry.”

Read the full article HERE.

Factive’s Director and Principal Consultant, Dean Laplonge, is currently exploring the link between masculinities and mining disasters for a chapter in his next book. To discuss this issue with Dean, contact him through our website.

New Factive Publication

The “un-womanly” attitudes of women in mining towards the environment

This paper asks a question: Do women have a better ethics of care towards the environment than men?

The answer to this question is an important one for the mining industry today. If the answer to the question is “yes”, the employment of more women in mining could bring about changes in the management of the environment within this industry; and an outcome of these changes could be a reduction in the pollution and damage caused by the ways humans currently mine the earth’s resources.

The debate about gender in mining regularly includes claims that the employment of more women will help change the industry. The article begins with the assertion that such claims rely on essentialist ideas about how all women behave, and fail to consider the production of masculinity as the preferred gender for all mining employees.

The article draws on the results of a survey (conducted by Factive in 2015) which explored the attitudes of women who work in mining towards the environment. It concludes that the sex of employees is not the best indicator of possible change in environmental management and practices in the industry. Instead, greater attention needs to be given to constructions of gender for men and women within mining, possibly by drawing on ecofeminist ideas.

“Instead of relying on women to save the mined environment, we should further challenge and change this gendered culture such that the environment benefits from a more feminist practice of mining.”

Access to the article is here. You can also contact Factive via our website to request a copy.

Reference: Laplonge, D. (2017). “The ‘unwomanly’ attitudes of women in mining towards the environment”. The Extractive Industries and Society. DOI: 10.1016/j.exis.2017.01.011

Gender inclusion in Canada report

The Mining Industry Human Resources Council in Canada has released its latest report on gender in the mining industry.

The study that informs the report adopted a traditional view of the gender model to explore how being a man or being a woman impacts on the experiences of people working in the mining industry. Almost 300 mining employees contributed through an online survey and interviews. They were asked about workplace culture, work-life integration, and career pathways.

The results include:

- Although the majority of women respondents rated their workplace positively, their experiences were less positive than men.

- Women are almost twice as likely as men to report difficulty in adapting to the mining culture.

- 70% of employees who had taken parental leave felt this had no impact on their career.

The report reveals some ongoing issues related to gender in the industry, while also showing some improvements, particularly in women’s experiences, when compared to previous similar reports. For example, while women still have a harder time fitting into the workplace culture of mining, employers appear to be making more effort to respond to issues that make work life more difficult for women.

Critical to the work that Factive carries out in this industry is the report’s recommendation to “Equip managers and employees with the skills required to create inclusive workplaces”. Numerous tools already exist to help achieve this outcome. Unfortunately, these tools are not often designed or deployed to encourage change in understandings and practices of gender. Instead, they can often unwittingly reinforce gender assumptions and practices, particularly when the intent is to encourage men to better support or to better look after women. In our experience, this approach does little to empower women in the workplace, and in fact works to sustain a model of gender that creates many of the problems to start with. The called-for “skills” should include awareness of how the traditional gender model (including how it works in the mining industry) often fosters exclusion.

The full report can be accessed here.

New paper: The mis(sed) management of gender in resource industries

Factive has published a new paper which comments on recent work which seeks to address women in extractive industries.

The purpose of this paper is to show the extent to which work on how to manage gender in resource industries fails to draw on the body of knowledge which explores gender in the workplace.

This paper explores the efficacy of a recently published toolkit within the context of the current debate about gender in resource industries (such as mining, and oil and gas).

The Australian Human Rights Commission’s toolkit speaks to this debate, but fails to analyse existing strategies to deal with the “gender problem”; it simply repeats them as successful examples of what to do. The authors of the toolkit also fail to ask a question which is fundamental to the success of any intervention into gender: what is the definition of “gender” on which the work is based?

Dean Laplonge , (2016) “A toolkit for women: the mis(sed) management of gender in resource industries”, Journal of Management Development, Vol. 35 Iss: 6, pp.802 – 813.

Women in Mining in Japan

Women who worked in Japanese underground mining faced a number of workplace challenges. Unequal pay, sexual harassment, and discrimination in job opportunities are no doubt familiar experiences for many women who work in mining around the world today. The situation for these women was doubly harsh, however, due to the conditions of the workplace and the insecurities they faced in their daily lives. They were required to work long shifts with little sleep, working in unsafe and unhealthy cramped spaces, with little or no assistance if they suffered an injury or fell sick. Their husbands who worked alongside them were often abusive and would gamble or drink away the household income. The men rarely assisted with family duties including ensuring there was sufficient food for the children.

W. Donald Burton’s Coal-Mining Women in Japan: Heavy Burdens offers an insight into what it was like to work as a woman in underground mining in Japan in the years between the Meiji restoration (1868) and the beginning of the country’s pre-war mobilization around the third decade of the twentieth century.

In many ways, the work conditions for female miners in Japan were no different from the men; and Burton acknowledges this at the beginning of the final chapter in his book. The female miners were akin to the male miners in the sense that they were part of the working class who shared the same impoverished social positions and the same treacherous physical workspaces. Burton’s book therefore offers a broader view of the mining industry in Japan over a 50 year period. It shows the divide between the power of the mining companies and the workers. The former were regularly supported by the state in their efforts to make profit while avoiding responsibility for accidents and injuries. The latter were forced to buy their own work tools, and were regularly in debt to the mining company that employed them.

For women who worked underground, however, there were additional challenges.

“…the daily work routines of Japanese coal-mining women left them with little, if any surplus time or energy to devote to these pursuits [eating, sleeping, study, entertainment]. On the contrary, those routines were guaranteed to enervate and sooner or later, destroy their bodies … That some survived into their seventies and eighties is a tribute to their hardiness and to the endurance of the women who carried the sena [coal baskets] and tebo [another kind of coal basket] and pulled the sura [sleigh or box filled with coal], all while accepting their family burdens…”

Burton draws extensively on stories told by women to help highlight the difficulties they faced not just as miners, but as female miners.

Biological differences meant that women had to work while menstruating with no access to fresh sanitary materials. There were no private washrooms for any of the miners underground. The heat forced them to work while wearing very few if any clothing. This left the women particularly vulnerable to sexual objectification and abuse.

Social and cultural differences meant the women rarely had any choice about where they could work or the kind of work they could do. They were often forced into working in the mines to pay off family debts. They were also forced to marry men so they could stay in employment. It was regularly the role of the woman to haul the heavy carts of coal out of the mine. A single woman had little chance of securing even this kind of harsh physical work.

After long shifts, sometimes with only a few hours of rest in-between, the women would have to cook for their husbands and look after the children who had been left unattended in a “crèche” near the entrance to the mine. The women tells stories of having to give birth underground. The heat of the mines and the arduous nature of their work often resulted in miscarriages or giving birth to dead babies. As one woman recounted:

“If a baby was born [in the mine], it would be wrapped in a ragged kimono, that’s all. If there was a miscarriage, it was common to put it [the fetus] on some straw sandals or newspapers. Then to go back to work as if nothing had happened.”

Burton’s account is a testimony to the women and their struggles. It is also a lament that they were unable to, and prevented from, translating their strength and resilience into something that could have benefited female workers in more sustainable ways over the long-term.

“…their gratification at having survived, their sense of accomplishment in getting out the coal and raising their children, their satisfaction at not being bested by the working conditions or by their menfolk, and their appreciation of the value of hard work formed the rudimentary basis of what might have become a class consciousness had they been able to benefit from modern organizational and bargaining weapons.”

Burton, W.D. (2014). Coal-Mining Women in Japan: Heavy Burdens. Oxford, Routledge.

Factive wishes to thank Routledge for supplying a review copy of this book.

Exploring the distance between ecofeminism and Women in Mining

Factive has published a new article exploring the possibility of a relationship between ecofeminism and the Women in Mining movement.

Abstract: While there is existing work on the relationship between gender and mining in strands of environmental and resource studies, this paper moves away from generic feminist analyses of the environment and gender. Turning to ecofeminism, I speak to a gap in the literature by examining a specific group of gendered actors— women involved in the Women in Mining (WIM) movement—under the lens of ecofeminism. WIM represents a liberal feminist demand for equal opportunities for women in the male-dominated mining industry. In its current iteration WIM has not located its work within ecofeminism nor have its key stakeholders identified as ecofeminists. Complex intersectionalities of race, poverty, gender, age, class, and ideo-geographies are often neglected. This paper queries, can ecofeminism and WIM enjoy a mutually beneficial relationship? The paper begins with a summary of how the epistemological lens of ecofeminism can offer new understandings of mining more generally. The next two sections present conceptual dialogues regarding how ecofeminism can challenge and reshape hegemonic practices and perspectives of WIM in its current iteration; and how WIM can inform and enrich our understandings and applications of ecofeminism. In closing, the paper reflects on the two schools as incompatible partners.

Reference: D. Laplonge, Exploring the distance between ecofeminism and Women in Mining (WIM), Extractive Industries and Society, 2016.

To request a copy of this published article, please contact us via our website.